Neurosequential Model Series - Part 1: Understanding Brain Regions

It’s common knowledge that our brains are complicated organs, and learning about the brain in relation to healing can feel overwhelming. Thankfully, Dr. Bruce Perry offers a digestible way to understand simplified regions of the brain, how each region is impacted by stress and trauma, and how to heal. For those who don’t know him, Dr. Perry is a child psychiatrist, trauma researcher, author, and speaker. His work has been revolutionary in helping us understand developmental trauma. During this four-part blog series, I’ll be breaking down each brain region, why this matters for creating understanding around trauma, and how to create healing and regulation.

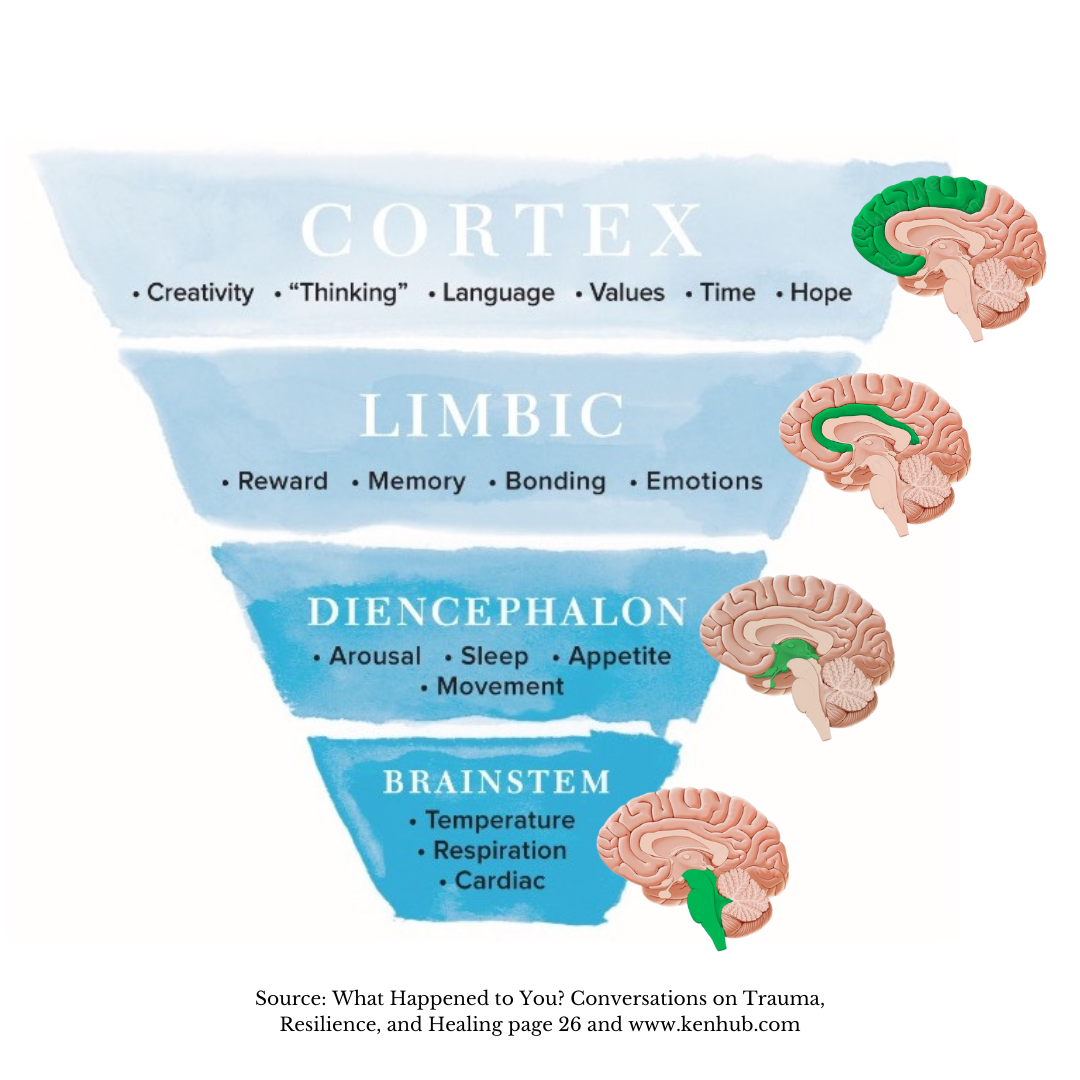

At its most simplified, the brain is broken up into four regions. The brainstem, the midbrain (also referred to as the diencephalon), the limbic system, and the cortex. Dr. Perry uses this diagram of an upside down triangle to represent his conceptualization of the brain regions. The upside-down triangle works for a couple of reasons: firstly, that is literally how the brain is stacked, the brainstem is on the bottom, with the midbrain on top, then the limbic system, and the cortex is the outmost, wrinkly, gray part of the brain. Secondly, using the upside down triangle represents mass and volume: the brainstem takes up the least space in the brain, while the cortex takes up the most. Before we break down these individual brain regions, it’s important to understand the brain develops from the bottom up and from the inside out, meaning our brainstem is the first region of our brain to be fully developed. Given that many of us are parents, or have spent time around children, it’s helpful to track a child’s development to illustrate brain development over time.

The Brainstem

The brainstem begins development in utero, is nearly fully formed by birth, and completes its development within the first six weeks of life. When thinking about all the things a newborn baby can do, we can easily understand the functions of the brainstem. Our brainstem controls all of the processes of our body we don’t have to consciously control. Our heart rate, body temperature, respiration, digestive functions, and perception of sensations like touch and sound are all controlled by the brainstem. These are all important functions, and need to be done automatically. Think about how much more brain power, and subsequent oxygen and metabolic resources, it would take if you had to consciously think about making your heart beat. Our brainstem is also reflexive, meaning it reacts almost instantaneously to signals of fear, distress, and danger; operating and reacting without conscious thought.

With this reflexive nature of the brainstem in mind, think about how we take care of infants: we’re focused on helping them feel physically safe, comfortable and connected, and soothing them when they are upset. Because the only available part of their brain is operating from instinct and the need for dependence to survive, our proximity and responsiveness helps them feel soothed and safe. Caregivers essentially act as an external nervous system, helping babies manage sensations and stress they can’t yet process on their own.

The Midbrain

As babies get a little older, they begin to have conscious control over their movements, which is due the development of the midbrain. The bulk of midbrain development occurs from around three months to three years. Our midbrain is responsible for our fine and gross motor movements, sensory processing, sleep, visual-motor integration, and motion planning, all of which is mostly unconscious to us as adults. However, for a six month old baby, think about all of the thought, planning, muscle engagement, and visual-motor integration it takes to see a toy, know they want to grab it, tense up their core for balance, extend their arm, grasp the object, and contract their muscles to bring that toy right into their little baby mouth.

When we caregive babies and toddlers at this stage, we’re encouraging them to practice these new skills engagement and play! We encourage them to crawl, walk, run, and jump, we get them into a sleep routine, and we try to help them understand how their body feels when it’s hungry or thirsty or tired. The more this part of the brain is used and the more robust those neural connections become, the more natural and fluid these skills become.

The Limbic System

Our limbic system is the next region to develop and completes its development in adolescence. The limbic system houses our emotions, our reward centers, our short term memory, and our stress-response system. With an elementary school aged child, they are not able to hold as much in their short term memory as a teen or adult, meaning they may need directions broken down into smaller chunks. They also can be much more emotionally reactive and unable to calm themselves down. They need guidance and practice related to empathy and relationships. Once the limbic system completes development, we become far less dependent on a caregiver to co-regulate with us. When we see teenagers pull away from their family and reduce their dependence on them, this is neurologically normal and appropriate, because they now have the neurological tools to manage those things more independently.

Caregiving for kiddos in this developmental stage includes helping them notice and communicate their emotions, with lots of scaffolding to help them experience success. Children benefit from explicit teaching and modeling around experiencing, naming, expressing, and managing their emotions when things happen that create a stress response. As children grow, they’re better able to do this themselves because they have the neural networks in place around calming down that you’ve helped them develop.

The Cortex

Our cortex is the last region of our brain to develop and doesn’t finish developing until around age 25. I always turn to teenagers to explain the functions of the cortex. Our cortex controls logical thought, emotional regulation, decision making, impulse control, time management, and all of our other executive functioning skills. Given that this region of a teenager’s brain is not fully developed, no wonder they lack all of those skills that make them so challenging! They are not able to fully think about the consequences of their actions and how things will play out in the future, which is why they often make silly choices over and over again.

When we are taking care of young people of these ages, our job is to model and explicitly teach how to do executive functioning tasks, and it’s even more beneficial if there are multiple adults available to do this, since we all have different ways of doing things that make the most sense for our unique brains. Our job is also to provide a soft place to land when they mess up so they can understand that mistakes are a powerful learning tool and don’t take away from their inherent value. By connecting with teens and young adults after they make a mistake, we’re helping them co-regulate and be soothed by an external nervous system, just like we did when they were babies.

Stay tuned for our next post of the series, where we’ll learn more about what happens to our brain in the short-term when we experience high stress or trauma, setting us up to learn about how trauma impacts our brain over time.